Rewatching Ritwik Ghatak's The Cloud Capped Star (1960) at the recent Third Cinema Days film festival (Tbilisi) was a captivating affair, particularly for the chance to watch it on the big screen. While striking shots of great, towering trees lining the embankment, under which Shankar sharpens his singing craft, take pride of place in providing the most iconic images of the film, towards the end of the piece I was struck by a different natural formation: that of the hills and mountains of Shillong.

Often the retreat up to the mountains is meant to signify a cessation of the trials and tribulations of ordinary life, a break for convalescence, a period of introspection and reconstruction both physical and mental. And here, too, Neeta is sent up to the scenic borderlands with China, in part, to recover from her bout of tuberculosis. Though in reality she is sent by her family to be kept out-of-sight, out-of-mind, her presence being a reminder of everything they have lost over the course of Partition, even while she steadfastly held the bereft family together.

In the process, her project of self-abnegation worked against her interests, both career-wise and romantically, and she was never able to gain the respect of her family; her submission to their needs was seen as derisory by all those that materially benefited from her work. Her physical worsening coincided with her loss of agency and status. In this context, the hills became a landscape of the uncanny and doom-laden as the camera eerily pans in a full-360 sweep, Neeta crushingly distraught.

This representation of the hills stands in contrast to the mainstream trope of elopement and romantic frolicking that is found rife across Hindi cinema. Often the Kashmiri mountains provide this backdrop, a fantastical, forbidden paradise evincing a national yearning – this motif firmly placed in a nationalist post-Partition amnesia and kept very much alive today.

Yet, I was also reminded of Forster's A Passage to India, and the ominous landscapes that portend misfortune, culminating in an off-screen mystery in the obscures of the caves. A carnivalesque trip gone darkly wrong:

As Himalayan India rose, this [Dravidian] India, the primal, has been depressed, and is slowly reentering the curve of the earth. It may be that in aeons to come an ocean will flow here too, and cover the sun-born rocks with slime. Meanwhile the plain of the Ganges encroaches on them with something of the sea's action. Their main mass is untouched, but at the edge their outposts have been cut off and stand knee-deep, throat-deep, in the advancing soil. There is something unspeakable in these outposts. They are like nothing else in the world, and a glimpse of them makes the breath catch. They rise abruptly, insanely, without the proportion that is kept by the wildest hills elsewhere, they bear no relation to anything dreamt or seen. To call them uncanny suggests ghosts, and they are older than all spirit. (E. M. Forster, A Passage to India [Penguin, 2015] p. 109)

Natural history itself is said to be endowed with a supernatural potency, residing at the level of the irrational and subconscious, between the mountain, river and hilly cave outposts.

At the centre of Ghatak's work, and echoed across orientalist aesthetics, is the role of the spiritual and the mystical in both the natural and social world. So, while Neetas position-without-identity leads to her tragic end, her brother Shankar is able to harness his voice to enter a contiguous zone of nothingness, but this site is rooted in a lineage of acting and being. His (male, upper caste) inheritance of Hindustani classical music is seen as a dalliance in the face of the modern facets of dislocation, institutional education and wage labour, yet he ultimately reaps rewards. Consistently through the film his vocal performances (the Raga Hansdhwani rendered by Pandit A. Kanan is of particular note) arrests the dialogue-heavy realism, pushing non-diegetic abstraction to the fore.

There is sorrow and transcendence and ontology here, surpassing the linear flow of the narrative. While Shakespearean tragedy, social realism, surrealism and Indian melodrama collide, the modal abstraction of the raga calls into question what really drives the film, as the descent of the empyrean crushes the soul and alters the narrational texture.

It is a crucial point for thinking about the relationship between politics and aesthetics, and the role of the social as a liberatory force vis-a-vis the problem of subjectivity itself, where sound and colour cannot be sealed within the rational actor. The Communist Party of India, elected to West Bengal governance at the time, would face forthcoming splits and challenges from the Naxalite Maoists; Ghatak's distancing from their political project, and studied focus on tragedy and aestheticism persists as a vital compass point. As the fascists continue to appropriate and weaponise the mythic and mystical, the many tributaries of spiritual form still drive social technologies that secular progressives, in their various stripes, have failed to fully comprehend and articulate as movers of history and social exchange.

Payal Kapadia's A Night of Knowing Nothing (2021) preceded the Ghatak screening at the festival, providing a chance to reflect on the contemporary politics of Indian cinema, and historicise the genealogy of New Wave, parallel Indian cinema. Kapadia's film is an oneiric take on the resistance to Modi’s BJP regime from 2014 until 2020. Much of the impetus stems from the BJP’s installation of an establishment figure into the presidency of the Film and Television Institute of India, the leading film school in the country. Through detailing the students protests to this government takeover, Kapadia expands the frame to incorporate various other marches culminating in the movement against the Citizenship Amendment Act (2019) which was seen as an enshrinement of anti-Muslim fervour. The protests, which were cut short by the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, were seen as wider movement against the hegemonic capture of civil society and a direct challenge to the increasingly Hindu nationalist (hindutva) politics that are tied to a strong neoliberal programme, oligarchical in nature.

Kapadia masterfully presents us this narrative in a hybrid form, interspersing found footage, news reports and protest imagery with brooding, slow shots of campus life. The narrative is threaded by an epistolary exchange between two lovers of different caste backgrounds. Their love is forbidden and transgressive. This aspect brings in an intimate sensuousness to add to the worthy political frame. There is an exchange of libidinality and energy found penetrating through social and political form, bringing the question of desire and social reproduction to the fore.

The film's ethereal quality, much of which is presented in grainy monochrome, portrays a field of aesthetic sociality where desire, resistance, image and story are being exchanged, explored and expounded across the film, across the campus, across the streets. This poeticism brings into the fold the very question of what the meaning of making cinema is in this context, what is the desire to do so, where can film-as-form take us. In this sense, Kapadia is making us reflect, metatextually, on the very tradition of filmmaking espoused within the FTII, both in aspects of filmic form and content.

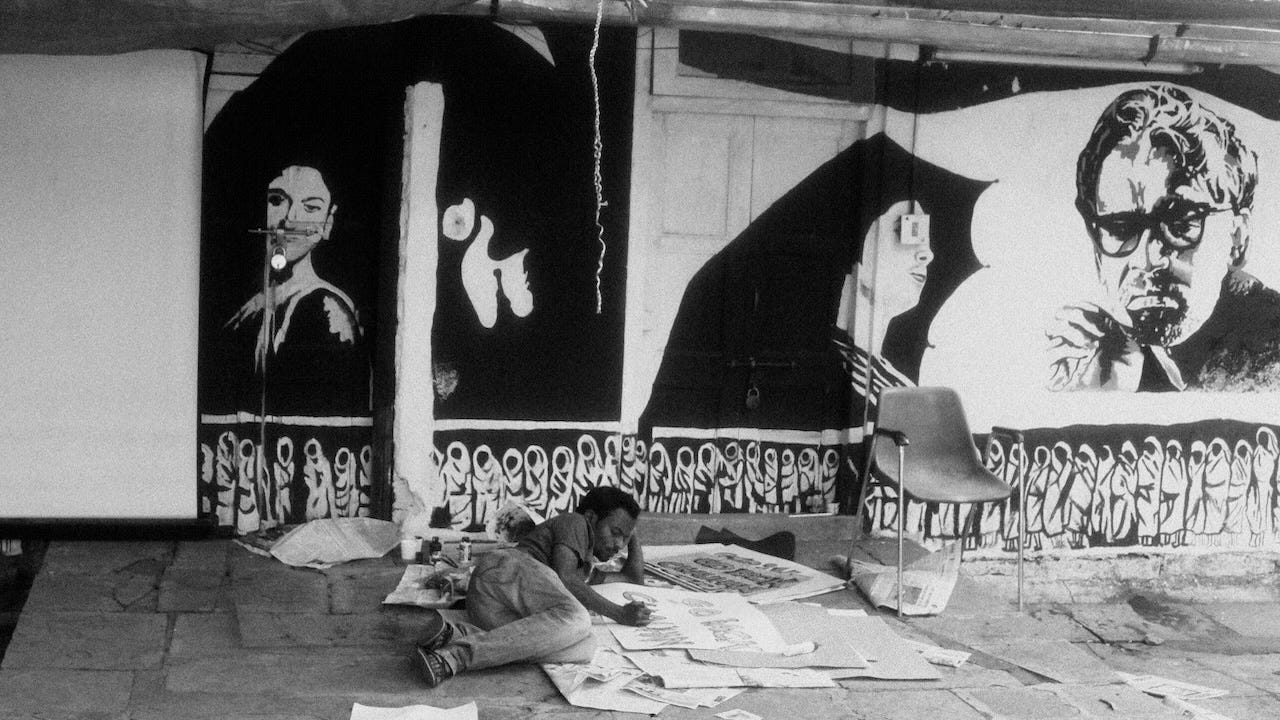

FTII, with the likes of Shyam Benegal and Mrinal Sen as previous presidents, is part of the tradition of secular, civic experimentation and provocation. Ghatak's film, as described above, represents an early landmark, alongside Satyajit Ray, in the establishment of this aesthetic movement. Ghatak in particular is pushing us to think about the limits of political subjecthood and national sovereignty through a poeticism that draws upon Western and Eastern touchstones, very much organically growing out of the more radical edges of an Anglicised Indian intellectual culture. Kapadia's hybrid documentary should be seen in this light, as reiteration of a radical tradition that extends right back into the debates between abstraction and figuration found abundant in the genealogy of Indian aesthetic discourse.

I often watch these slow Indian films as a way of trying to access some cultural meaning that might be hidden in the recesses of my subjectivity. It's a futile affair of course, but the time-stretched sparse nature of such work does go some way towards a sort of revealing – ontological or otherwise. Something like planting memories I never had of a forgotten part of my history. There's something here about the specificities of cultural identity, but also a more general revisiting of the self, with each repeated iteration an alteration takes place, a fine-tuning of interiority and perception, I would venture, as I look out onto the mountain and its golden ridges fringed with shadow and gloss

.