It’s Just not Cricket

England vs India and the interminable drift to death

It all begins with cricket. And ends with the people. Or the other way. There is a correlation. I am sure of it. And the epic narrative of it all sits out there somewhere amongst all the dread, spirits, guts and gall. Against time compression, the emergence of AI, the mind-numbingness of digital immersion, test cricket persists, an archaic bulwark against oversaturation and the fleetingness of contemporary life. And with one of the great series of recent times wrapping up in superb style in south London at the Kennington Oval–India sharing the glory with England–one has to turn back to its magnificence.

This thing commands your attention. Sit in amongst it and weep. Pour over the stats, the weather conditions, the weird knacks that each bowler seems to have, the vagaries of the ball’s condition. Let these players become characters in your life. Parse through their biographies. Sit here, listen, watch, read: for five days, for six weeks, do nothing else. Hold your attention on the minute detail and dot balls that could mean everything to everyone. To me at least. Wait for Siraj to rip another one; for Root to guide it down for four; for Krishna to pulse in for another spell; Woakes to hobble along; Pant to fly forwards. All to dulcet, learned tones set upon the verdant carpet.

CLR James talks about cricket, and the emergence of sport more generally, as part of the great democratic initiative that took place in the late nineteenth century. The skills, discipline and modalities of teamwork required correlated with an increasingly organised form of civic engagement, manifesting in the various antagonisms of class, race, economic and state structure that typified capitalist development in its more liberal formation. This formulation of James’ comes hand-in-hand with the development of education as a liberating tool, of the will to consciousness of the individual subject that produced increased ambitions across the classes. But the democratic initiative was one also riven with exploitation and the degradation of proletarian and subaltern life. This is perhaps the great antagonistic contradiction of the development of the social state–with greater centralisation the ability for social and intellectual engagement is increased, while simultaneously formalising subjugation through rational economic mechanisms.

Literacy and literature, too, developed in this period, and the development of cricket specifically cannot be disentangled from its relationship to writing; poetic narration as a central part of the game; its culture, allure, grasp of the human psyche. And summer, always summer. Various iterations of the English summer playing out across the globe. Various iterations of English village life morphed to localities, from Old Trafford to Kolkata's Eden Gardens, Jamaica's Sabina Park to the SCG. But this globalised conservatism, replete with its remaining adornments redolent of the zenith of high imperialism, one feels increasing cognitive dissonance.

Is this the truth of postmodernism? The archaic clashing with the hegemonic; test cricket and instagram reels; over-by-over reports and facebook comments; commentator’s furore and a bit of needle – it's just not cricket. That old Victorian adage still ruling the day; the gentleman’s game holding firm. A temporality both of its own and fully complicit with a conservatism of force; can we think about the rearticulation of desire here? Something akin to the traditionalist turn back to the IRL art object. Time well spent, up close, textured, immersed. Nothing innovative. The rules are good enough, the boundaries not needed to be broken, just further explored. Classical sport. Bonafide theatre. The sporting arts, if you will.

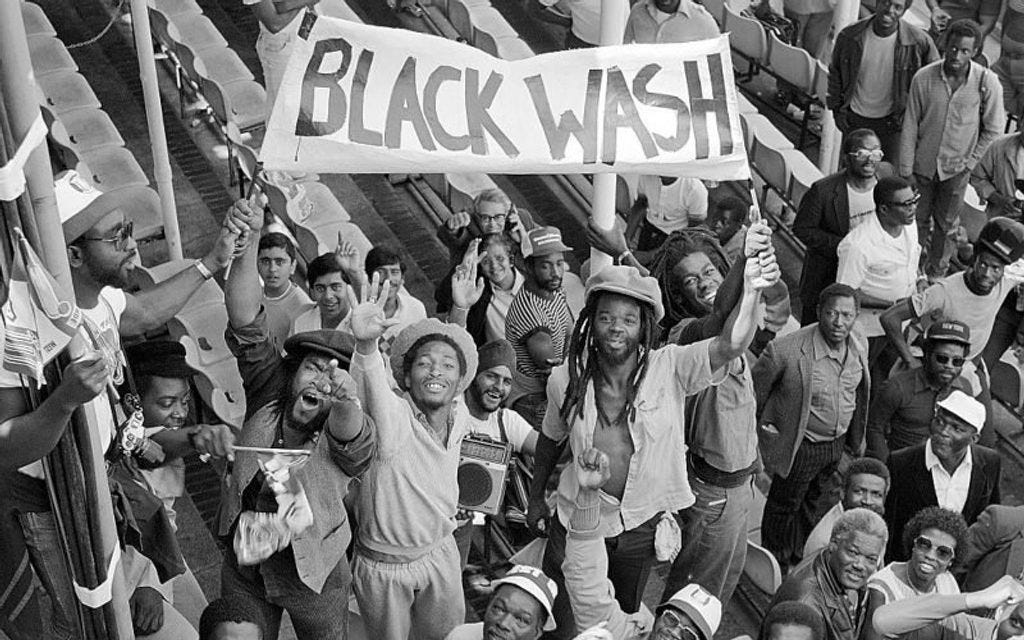

Let's think about a contemporary reality. Bazball is seen as a reinvention of the England team, from a dull, meandering team under Joe Root and Chris Silverwood through to the rush of blood under Brendon McCullum and Ben Stokes. Their emphasis on animal spirits, risk, assertion and passion seemed revolutionary and novel. We had seen the West Indies teams of the 1970s and 80s, and Australian teams of the 90s–imitated somewhat by India under Virat Kohli–provide fire and brimstone before, but this tack from England feels different. The imperial core, for once, seems to be tackling the problem head-on.

Amidst all the postcolonial melancholy, the contemporary descent into mediocrity and glumness–right from the 1950s through to 2016 Brexit vote–Baz has managed to reenergise one of the oldest institutions still worthy of popular staging. For this is a great carnivalesque stage–the Ashes of 2005 provided narratives, thrills and drama that arguably no national football–or otherwise–success could ever match. (London 2012 was a different sort of civic circus.)

Is this postcolonial sanity? A realistic embrace of assertion and mediocrity. Is Zak Crawley our lord and saviour? England conceived as a bit more self-aware, understanding that the rot was always there, and reevaluating the truly excellent elements. Test cricket is always dying. That's part of its identity. And we wouldn't have it any other way. Perhaps England is always dying. And we shouldn't have it any other way. The lurch to almost disappear, to be overawed by the new powers–Western and Eastern–and make that calculated embrace of the archaic and popular. Is this reasonable, grown up England? I suspect not, but it's worth chewing over.

All this took place in the background of a historic India-UK free trade deal, the first of its kind. India flexing its muscle. New corporate power, the centralisation of its labour power, financialisation, oligarchy, a world of multi-alignments. The UK as just another partner of many, if now with slightly more privileged access to its markets. The Indian Premier League as the great scourge of test cricket. The new shiny short-form of the game, full of fireworks and music and unnecessary colour.

Yet India has managed to maintain balance between the short and long form on its own terms, while monopolising the market. Without it, though, would we have seen the emergence of Muhammad Siraj, the great lionheart of India, or the flamboyance of Rishabh Pant? Surely Indian cricket would still be dominated by the Marathi, Tamil and Bengali elites? Capitalism, in its liberatory capacity, shakes things up, albeit along predetermined lines.

But we are also seeing new masculinities. Kohli led this sharper, more recalcitrant disposition, reminiscent of the Chinese communist spokespeople, a sort of racialised overcompensation loosely extracted from anticolonial feeling while really pushing a right-wing nationalist ideology. The humiliation of the nineteenth century assimilated as national myth and authoritarian cudgel. Baz and Ben's England comes out as rather parochial and gentile in contrast. Minor discursive crises amidst the slow decline. Reflective of Starmer's Britain?

George Bernard Shaw says somewhere that the English, not being a particularly spiritual people, had to invent cricket to gain a sense of eternity. We are increasingly driven to think of duration as a problem in modern times, instancy as virtue. Test cricket is a stalwart reminder of the importance of duration, concentration, ritual as vital lifeforce. So there is conjuncture and discourse, and then there's this other thing, that interminable thing. Let's stick with that, or just merely accept the embrace of its omnipresence. Culture sits across both camps. Narrative and viewership as both spontaneous, raw, while also formalised, bound. Test cricket is dying, Such is life.

A erudite, wonderful, I'm tempted to say a sprawling piece (although that is true of many Substack posts) that presents the demise and stoicism of test cricket as the continuation of the contractions of colonialism, late nineteenth century conservatism as it meets the gross spectacle of contemporary culture, friction free capitalism the IPL and the idiocy of the Hundred (who the fuck thought that was a good idea even within short form cricket?!). Isn't the anachronism of test cricket the symptom of a legacy form that is unable to give up its charm, as a nostalgia that gives a sense of a noble past - like collecting vinyl, or vintage cloths, a repackaging of what is in demise, notwithstanding the brilliant England-India series, a singularity of a form that is continually that is barely resisting its own postmodern packaging and commodification. I love test cricket, but I hate to say it, and it might be a form of contemporary Orientalism, as the centre of gravity moves east to Modiland, the game, as you say is caught up in a fervent nationalism (wasn't it always?) and Bollywoodisation of the cultural economy, test cricket is slowly losing its splendid ritualism - like the cultural anachronism of the Japanese tea ceremony. I admit this is an obvious thing to say, but my melancholic pessimism is of an old man that lived through the glory days of the West Indies in the 70s anti-colonialism. The demise of cricket there is a telling sign. The emergence of Afghanistan cricket is a great story of cultural resistance against the barbarity of the Taliban, but a minor scene of the entanglement of cricket and global empire. As it always was. I'm not sure as the world heads to apocalyptic self destruction with genocidal war as horror entertainment, and the slow death of the planet test cricket is like the scene in Carry Up the Khyber where as the Afghan forces are invading the black tie dinner party continues. We are screwed, Test cricket is an imagined bunker, like a hospital in Gaza, waiting to be bombed into oblivion. (If only the Zionists played test cricket). As usual south London maybe the only place Test Cricket will survive, where the banal everyday culture, indifferent to the world, is an irrelevant invisibility that resists the charms of postmodern AI glitter. Loved the post.

*genteel?